Repercussion Section: The Intended Consequences of the Permian Basin (Part II)

by Sandra Steingraber, SEHN senior scientist and writer in residence

In September 2025, I traveled to West Texas to join Sharon Wilson and Miguel Escoto of Oilfield Witness on a three-day fact-finding tour of the nation’s leading oil-extracting region, the Permian Basin, which has allowed the United States to become the world’s number one oil producer. Fully half of all U.S. crude oil is extracted from the Permian. Intensely fracked, the Permian Basin is also the one of the world’s top sources of greenhouse gases, particularly methane. The Permian Basin is a planetary carbon bomb whose emissions are visible from space via satellite imaging, and also via Optical Gas Imaging cameras, which Oilfield Witness uses on the ground to reveal the fossil fuel industry’s false narratives about this place.

On the final day, we were joined by a delegation of legislators from Mexico’s General Congress—specifically from the Chamber of Deputies—activists with the Mexican Alliance Against Fracking (Alianza Mexicana contra el Fracking), and a videography team.

The legislators were deeply moved by what they saw. And on October 15, we all met again at a forum on fracking that took place within the Mexican Congress at which time the four senators introduced a legislative initiative to ban fracking in Mexico.

This is the second part of a two-part series.

Last month, we looked closely at the very intentional consequences for West Texas of Texan oil magnate George Mitchell’s 15-year attempt to avoid financial ruin by extracting more gas and oil out of his fast-depleting wells.

In 1997, he succeeded wildly by combining two experimental techniques—fracking and horizontal drilling—and by swapping out expensive fracking gels for plain old water, which shouldn’t be cheap and freely available to Texas drillers but was.

And still is.

Horizontal drilling allows boreholes to penetrate shale layers miles below the surface of the earth and then extend sideways through those layers where bubbles or oil and gas are trapped.

Fracking uses explosives plus pressurized fresh water to blast apart those shale layers and shoot into them grains of sand to prop open the cracks so that the gas and oil can flow out and up to the surface.

Mitchell didn’t invent fracking or horizontal drilling, but he did yoke them together, commercialize the technique, and scale it up, enabling him, fifteen years later, to die a very rich man.

Horizontal, high-volume hydraulic fracturing went on to transform a whole swath of Texas and New Mexico—300 miles long and 250 miles wide—into a fossil fuel sacrifice zone and also went on to rename this region the Permian Basin after a subterranean landscape that no one has ever seen and that was formed during the Paleozoic Era.

More specifically, the Permian Basin represents a vast underground coral reef that formed in a shallow ocean that once covered this part of the world. When it fossilized into shale, the corpses of the abundant marine organisms that inhabited this reef became trapped inside and turned into a cache of hydrocarbon molecules we call crude oil and natural gas.

***

Last month, Oilfield Witness invited me on a fact-finding tour of the Permian Basin. On the third day, we were joined by four legislators from Mexico’s Chamber of Deputies, which is analogous to our U.S. House of Representatives, and a videography team who documented our road trip.

We all crammed into a van and drove on backroads for hundreds of miles through the Basin, stopping to examine oil wells, gas wells, injection wells for fracking waste, flare stacks, gas processing facilities, compressor stations, waste pits, pipeline construction projects, water stations, and man camps.

Essentially, the Permian Basin is an outdoor factory the size of Florida. Fracking infrastructure seemingly went on forever, covering cotton fields and ranches, and even though we were mostly out of cell phone range in a remote landscape—it’s a five-hour drive between Midland and El Paso—the air quality and the decibel levels were more like Newark Airport than home on the range where the deer and the antelope roam. (See part 1 for a detailed description.)

At each stop, we all piled out of the van together and stood silently, breathing the acrid air, taking in the devastation, struggling with burning noses and sore throats. We asked questions in English and Spanish of our Oilfield Witness hosts. On request, I gave mini-presentations, translated into Spanish, on groundwater, on air pollution, and on what we know about the health harms of chemicals to which we were now being exposed.

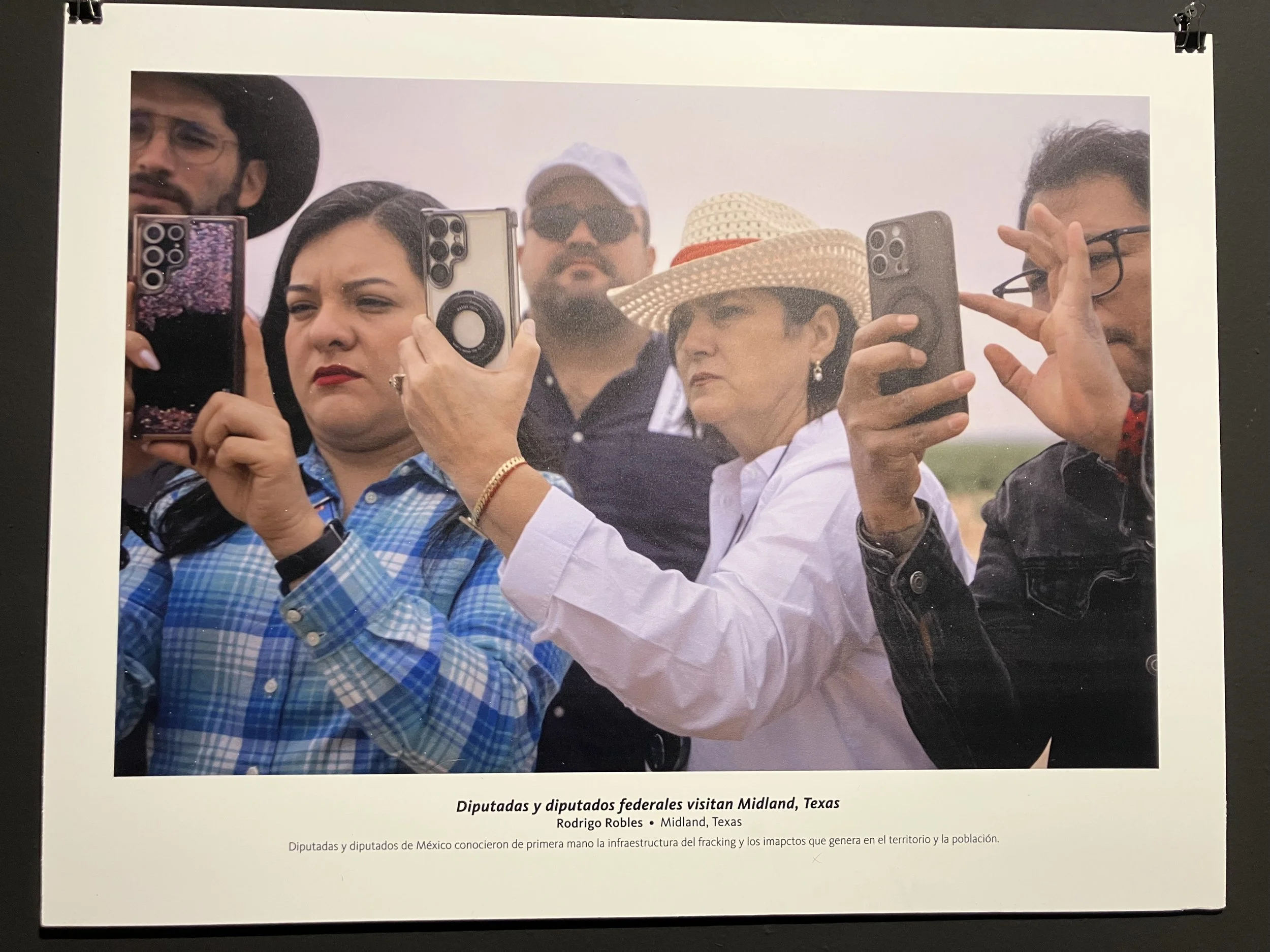

And we took pictures. So many pictures.

Later that evening, back in the hotel conference room, we convened a seminar. I presented the main findings from our fracking science compendium. Sharon Wilson of Oilfield Witness presented extensive video from her FLIR camera that makes visible massive methane plumes and releases of benzene and other hydrocarbons pouring forth from all the equipment, including pieces of infrastructure that looked idle or abandoned.

Photo of a photo. A exhibit on fracking inside the General Congress of the United Mexican States in October 2025 included this photo of Mexican legislators visiting the oilfields of the Permian Basin in West Texas during their fact-finding tour in September. Photo credit: Sandra Steingraber

***

Ironically, one of the consequences of the prodigious productivity of the Permian Basin is a renewed push for widespread fracking in Mexico itself, as fracking has come to represent independence from U.S. gas imports and all the potential political leverage that the White House can exert.

A brief history: In the 1920s, Mexico was the world’s second leading producer of oil. Its reserves were extracted by foreign-owned oil companies, including Royal Dutch/Shell and Standard Oil of California (now Chevron). Then came the Great Depression, a global oil glut, labor unrest, and a strike by Mexico’s oil workers.

The foreign companies refused to abide by a decision of the Mexican Supreme Court to settle the problem, and then-President Lazaro Cardenas, siding with the workers, responded in stunning fashion. In 1938, Mexico expropriated oil assets, closing its doors to foreign oil companies and creating a state-owned oil monopoly called Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX).

This decision itself led to all kinds of unintended consequences, one of which was the severing of diplomat relationships with Great Britain after the oil companies that were kicked out of Mexico retaliated with an embargo of Mexican oil and Mexico’s major buyer became… Nazi Germany. But, in general, as the Mexican delegates explained to me, the creation of PEMEX was, and remains, a symbol of Mexican sovereignty and a point of national pride.

Fast forward to 2014 when Mexico ended the financially struggling PEMEX monopoly through legislative reforms that permitted foreign investments in oil and gas via profit-sharing contracts. These reforms opened the door to companies with, among other things, technology and expertise in shale gas extraction via fracking.

And then skip ahead to 2018. Newly elected President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, of the left-leaning party Morena, announced a suspension of all further energy auctions for three years, temporarily halting, on paper, permits for new fracking operations. This announcement was widely seen as a possible step by Obrador toward fulfilling his campaign promise to ban fracking in Mexico.

But laws were not passed, and by 2023, it was clear that fracking was indeed taking place in Mexico, in at least a soft-launch way, although it was obscured by calling it by alternative names, such as “stimulation of in complex geological deposits.”

The next year, 2024, Claudia Sheinbaum, a bona fide climate scientist who contributed to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change and has published more than a hundred papers on sustainability, became the president of Mexico. Sheinbaum ran as a Morena party candidate and won her election in a landslide.

You might imagine, then, that her election would finally fulfill the promise of her predecessor to end fracking in Mexico once and for all. But, in fact, the opposite is happening.

In August, the government released its 10-year strategic plan for PEMEX, now deeply in debt, and it reveals plans to double down on fracking. As the Spanish newspaper El País described the focus of the strategic plan:

One of its main measures is to “reactivate the evaluation of complex geology deposits” to increase the country’s meager oil reserves. The only way to do this, however, is through hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, a technique criticized by environmentalists. Another example is the 2025–2030 Plan for Strengthening and Expanding the National Electricity System, which lists 35 new power generation plants, most of which rely on hydrocarbons such as natural gas.

Adding to the push to expand fracking in Mexico is growing unease at its reliance on fracked gas from the Texas Permian basin, which is currently its major supplier. “Amid heightened tensions with the Trump administration over everything from trade to security and immigration, gas flows could become a flash point if talks turn sour,” according to Bloomberg.

From this point of view, fracking is sovereignty. Fracking is the anti-Trump position.

***

An Indigenous leader speaks at a press conference, detailing the harm that fracking has brought to his community in northern Mexico, October 15, 2025. Photo credit: Sandra Steingraber

The Mexican legislators who toured the Permian Basin in September—and who included members of both of the dominant political parties—went back to Mexico City and did two things.

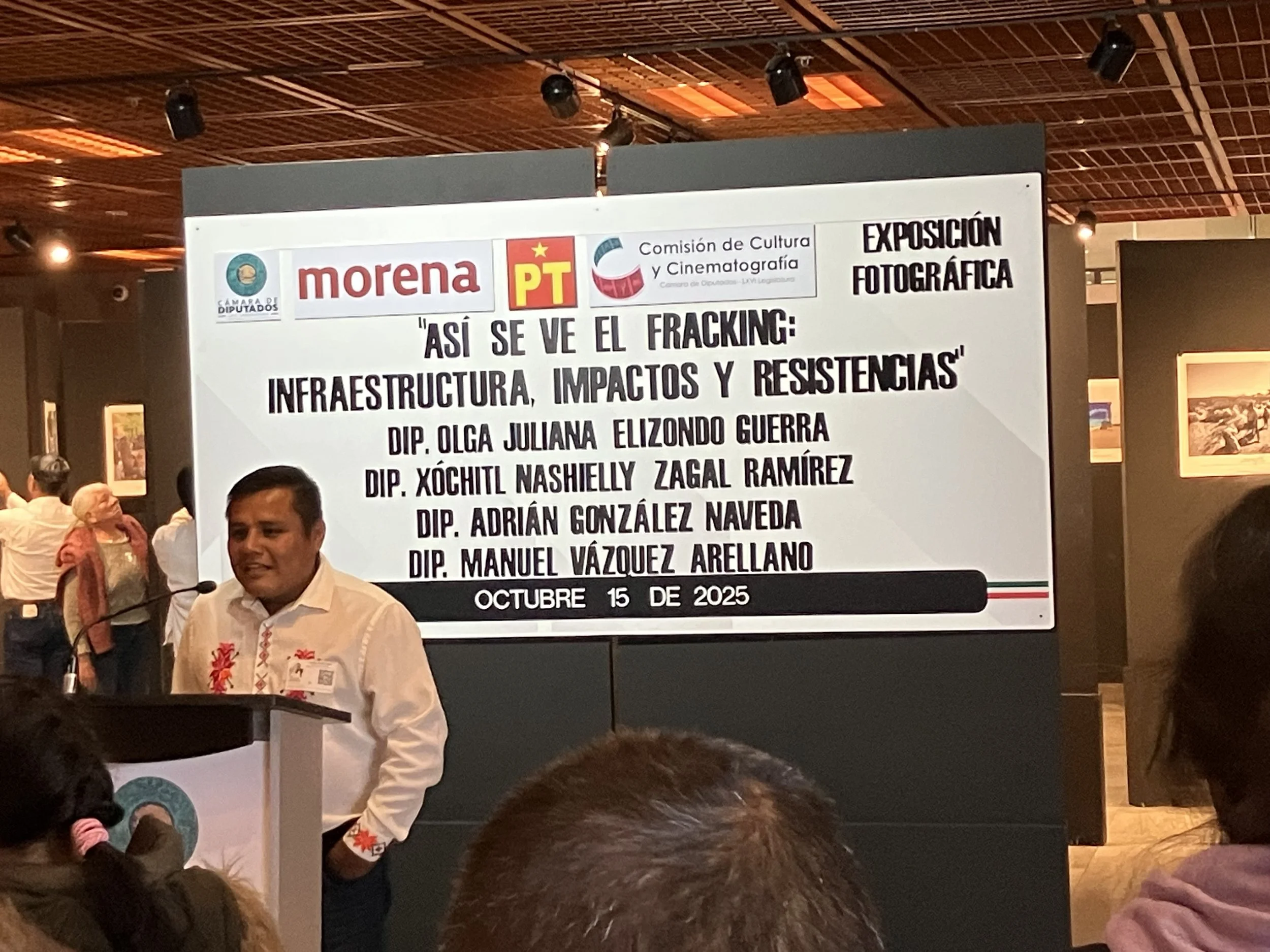

First, on October 15, they hosted a Congressional forum on fracking in Mexico, complete with a photography exhibit that included many of the images from our fact-finding mission to the Permian Basin that illustrated the horrors of fracking.

And second, at the end of that forum, the legislators introduced an initiative to ban fracking that would take the form of an amendment to the law and Constitution. Their proposal was immediately co-endorsed by two additional legislators.

I was invited to testify at the forum about the health and climate damage caused by drilling and fracking activities in the United States. In my remarks, I emphasized the inability of rules and regulations to make fracking safe. Its many dangers, I argued, were systemic and unfixable, from radioactive releases and earthquakes, to water contamination and toxic air pollution. These are the same intractable problems, I pointed out, that compelled New York State to ban fracking in 2014. And the data has only become stronger since then.

Sharon Wilson of Oilfield Witness also testified and showed her video evidence of fracking’s immense harm to the Permian Basin. Sharon opened her testimony by saying plainly, “I am here so you won’t make the same mistake that we made in Texas….If people could see the pollution from oil and gas with their bare eyes, it would have ended with the first well fracked in 1996.”

Sharon Wilson of Oilfield Witness looks on as journalists and legislators tour the fracking photography exhibit in the Mexican Congress, October 15, 2025. Photo credit: Sandra Steingraber

In addition, various Mexican energy experts addressed the Congressional forum about shale gas extraction, making the case that fracking is a false answer to the problem of energy sovereignty in Mexico. They noted that the productivity of individual fracked wells in the United States is actually quite low and rapidly decreases over time, “leading to the need to exploit and drill ever more wells over a vast areas.”

They alleged that four times more investment was required per barrel of oil when fracking is the technique used for extraction. And they argued that fracking holds out a low chance for energy sovereignty because PEMEX must still depend on U.S. companies to do the actual work of fracking. The end result, they said, would be only a few years of oil and represent “the transfer of impacts from one side of the border to the other.”

Most moving were the testimonies given by the leaders of two different indigenous communities: the Teenek People, who live in the north-central state of San Luis Potosi, and the Tutunaku People of Papantla in the eastern state of Veracruz. Both territories are targeted by fracking operations, and their spokespeople described in detail the ongoing damage from previous fracking operations that they have witnessed firsthand: Unreported water withdrawals from the San Juan River. Seismic activity. Lakes and streams that have dried up and never recovered. Permanent deficits in two aquifers.

These are damages, they emphasized, for which the oil industry has offered no compensation. “Our lands are sacrificial zones.”

Said one, “We are organizing ourselves to stop fracking. For us, water is sacred. It is the veins of Mother Earth.”

Said another, even more starkly, “It is a genocide.”

Representing the Mexican Alliance Against Fracking, Alejandra Jimenez urged the gathered legislators to find the courage of their convictions. “PEMEX’s plan most not come to fruition. It is hiding the word fracking in its document and using euphemisms, but we are not going to step back….Fracking does not have a social license and it will never have one.”

And as for the legislators, they also spoke movingly in their lead-up to announcing new proposed legislation that would put end to fracking once and for all. One noted that while no fracking ban law had been enacted, “we can say that fracking was contained up until now.”

“Dear colleagues, we cannot get both gas and oil by this technique and also have a future for our children. We cannot achieve sovereignty by this technique. Our dignity lies in defending our people. We have listened to all of your demands.”

After four hours of testimonies and announcements, we filed out of the Congressional hall to attend a press conference where all of the above talking points would be presented to awaiting journalists.

En route, I asked an anti-fracking activist what she thought of the forum’s outcome. Her response: “We know it is easy for elected officials to please people and propose legislation. They want to win votes. Now we must make them fight.”