Repercussion Section: Formosa Plastics and the Necessity Defense

by Sandra Steingraber, SEHN senior scientist and writer in residence

I was born in central Illinois. Which means I grew up not far from the funny-sounding village of Illiopolis, which is situated in the open prairie, in the exact cartographic middle of the state.

Siting it there was an intentional attempt to mimic the success of Indianapolis, which is located in the exact center of the neighboring state of Indiana. Neither metropolis is located on a navigable waterway, but Indianapolis became the state capital while Illiopolis (population 839) remained an isolated, rural curiosity.

Until 1942.

Soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government bought 20,000 acres of prime farmland that abutted the west end of Illiopolis, evicted the landowners against their objections, sent in 15,000 construction workers, and turned the community into a war machine.

For three years, Illinois was the nation’s leading producer of ammunition, and the Sangamon Ordnance Plant in Illiopolis was the crown jewel of the effort, turning out shells, bombs, bomb fuses, propellants, boosters, and anti-tank rounds as part of a 24/7 wartime operation.

Illiopolis was chosen as the hub for all this munitions manufacturing as much for its isolation—if something blew up, all the surrounding emptiness would serve as a safety buffer—as for the plentiful groundwater and the railroad tracks that ran through it.

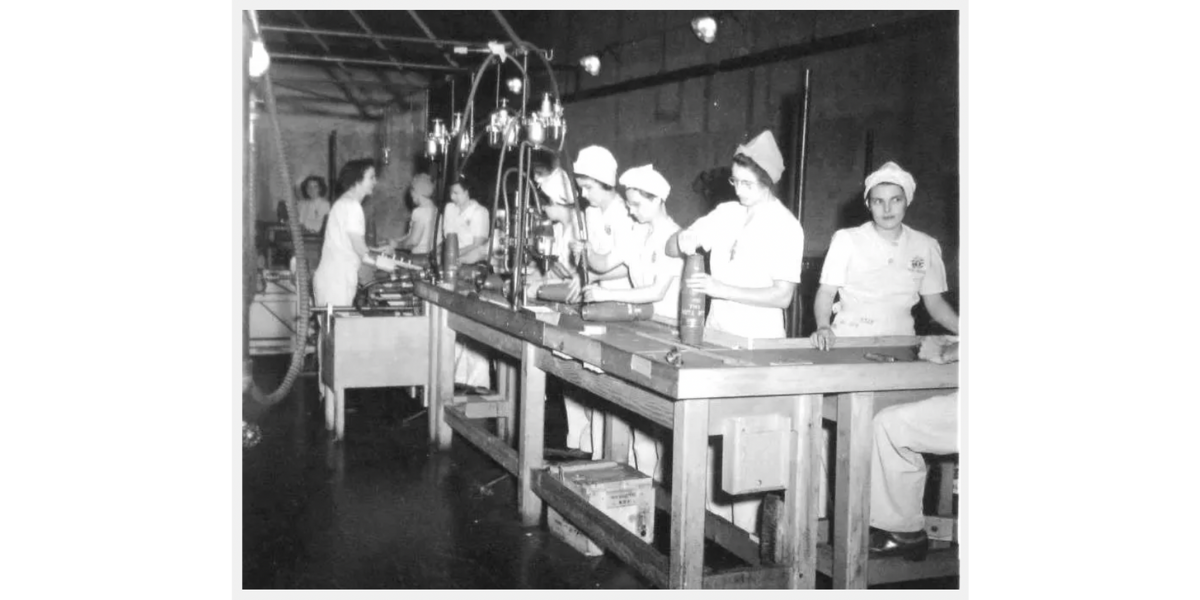

‘WOWs’ (Women Ordnance Workers) prepare boosters at the Sangamon Ordnance Plant. https://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/sangamon-ordnance-plant/

The operation ended as abruptly as it began.

Two weeks after V-J Day, on September 6, 1945, the Sangamon Ordnance Plant, with its 2,000-plus buildings, was declared surplus and sold in parts at fire-sale prices. Parts of the property were heavily contaminated and, to this day, remain a military ghost town.

In 1953, Borden Chemical bought a chunk of the plant and began manufacturing, among other things, Elmer’s glue.

Here is where my own childhood intersects with Illiopolis. In elementary school in the 1960s, my friends and I were all proud of the fact that the glue in our orange-capped plastic bottles emblazoned with Elsie the Cow was made just down the highway. We imagined railroad tankers, full of gooey white Elmer’s, heading out from Illiopolis to schoolrooms across America.

***

In 2002, Borden Chemical was bought out by the Formosa Plastics Corporation, a subsidiary of the Formosa Plastics Group, which is headquartered in Taiwan. And this is how the tiny farming community of Illiopolis—neither north nor south, neither east nor west—became a major national supplier of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) resin, servicing the three kingpins of vinyl flooring: Armstrong, Congoleum, and Mannington.

From bombs to glue to kitchen tiles.

PVC plants are among the nation’s worst polluters. Almost immediately, the data from the Toxics Release Industry began to show that the Illiopolis plant would be no exception.

In 2002, Formosa produced 200 million pounds of PVC resin and released into the air 31,000 pounds of vinyl choride and 45,000 pounds of vinyl acetate. Both are the vaporous feedstocks for PVC plastic. Both are human carcinogens.

And this is how Illiopolis—otherwise surrounded by corn and soybean fields—landed in the 90th percentile in the nation for air releases of cancer-causing substances.

Formosa occupied Illiopolis for three years—just about as long as the U.S. government had sixty years prior. By 2004, it had ceased operations. But during its brief tenure, Formosa Plastics managed to accomplish something that three years of bomb-making during World War II never did.

It blew up.

At 10:40 p.m. on April 23, 2004, Formosa Plastics’ PVC plant in Illiopolis, Illinois exploded, sending into the night sky a 100-foot fireball and killing four workers. A fifth would die in a hospital burn unit 20 days later.

Four towns were evacuated, several highways closed, a no-fly zone declared, and 300 firefighters from 27 communities battled the flames for three days. Their efforts were complicated by the power outage, triggered by the shock wave, that disabled the water supply.

Formosa Plastics ran the wells that provided the town’s water.

By the time the fire was extinguished, the plant was destroyed, as was an adjacent warehouse full of PVC resins. Burning PVC creates dioxin, one of the most potent chemical toxicants ever synthesized from fossil fuels.

The U.S. Chemical Safety Board (CSB) was summoned to determine the cause of the explosion. After a three-year investigation, the board announced two findings: 1) the cause of the blast was human error—a worker had become confused and opened the wrong valve at the wrong time—and 2) Formosa was aware of such a possibility but had failed to take action to prevent it.

In public statements during the stunned days following the blast, Formosa promised to rebuild the Illiopolis plant, the town’s biggest employer.

It did not. And after a decade of existence as an abandoned, hulking, toxic, burned-out ruin, Formosa’s Illiopolis facility was finally demolished in 2014.

Formosa Plastics vinyl chloride explosion, https://www.csb.gov/formosa-plastics-vinyl-chloride-explosion/

***

Illiopolis, Illinois is not the only community that has suffered at the hands of Formosa Plastics.

In environmental justice circles, Formosa is known as a “serial polluter.” Not only is it one of the world’s largest creators of plastic, the company regularly contaminates communities where its facilities are located and is undeterred by legal settlements and financial penalties, according to attorney Bennett Zurofsky.

In April 2016, a spill of chemicals, including cyanide, at a Formosa Plastics steel plant destroyed marine fishing habitat in Ha Tinh, Vietnam, and ruined the livelihoods of fishermen and tourism workers.

The resulting environmental disaster is considered the worst in Vietnam’s history, with more than 4 million residents harmed.

In the end, Formosa paid $500 million to the Vietnamese government, but the victims themselves, who have sued, have yet to be directly compensated or even win a full, independent investigation of the accident. Additionally, Vietnamese activists remain in prison for organizing protests about the disaster, with one serving a 14-year sentence.

Here in the United States, Formosa has a long history of violating environmental laws, paying fines, and blithely carrying on, including at its Texas plant where plastic pellets and other pollutants have been repeatedly spilled into Lavaca Bay.

Even after penalties of $50 million and $30 million, plus an agreement to comply with zero discharge of all plastics in the future and to clean up existing pollution, the company has racked up 700 new violations under the Clean Water Act. Formosa is also planning to locate a $12 billion petrochemical plant in the environmental justice community of St. James Parish, Louisiana, in the heart of Cancer Alley.

***

The U.S. headquarters of Formosa Plastics Corporation is in Livingston, New Jersey. In August 2024, 70 protesters—including faith leaders and environmental justice leaders— gathered there and, in an act of civil disobedience, blocked the entrance. Six were arrested, and four decided to proceed to trial.

One of the four was Diane Wilson, Texas shrimp boat captain, Goldman Environmental Prize winner, and longtime foe of Formosa Plastics who had helped win the $50 million settlement against the company in 2019. Whose terms the company was now violating.

***

And here is where the story has a happy ending.

The Formosa Four sought to use the necessity defense in court. The defense of necessity argues that a criminal act committed during an emergency is justified because the harm done by not taking this action is greater than the harm caused by the action itself.

Breaking into someone’s house to grab and remove a child because the house is on fire is a classic example. The Formosa Four hoped to argue that Formosa Plastics’ ongoing harm to the environment and public health in Texas, Louisiana, and beyond, justified their act of blocking an employee entrance for a day.

The application of the necessity defense is limited by several requirements. One of them is that the defendant must have had no realistic alternative to completing the criminal act. In other words, the defendant must demonstrate that all legal remedies to averting harm had been exhausted or would not have worked.

The Livingston Municipal Court refused to allow the necessity defense. But the Formosa Four appealed, and, in April 2025, New Jersey Superior Court reversed the Municipal Court’s denial.

In his ruling, Judge Arthur Batista Judge Batista said, “It is clear to this court, that these appellants have presented compelling grounds to allow the affirmative defense of necessity - justification to be raised at trial.”

And then, last month in June, just as the trial was about to begin, something else happened: the prosecutor decided to dismiss all the charges, “explaining that the State would be unable to meet its burden of proving them guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Here is defendant Diane Wilson with the last victorious word:

This dismissal is just another win in the long fight against Formosa Plastics and the damage they continue to do to Texas’s environment and fishing communities. While this decision is a victory, I will not stop taking on this serial polluter that thinks it is above the law, and I will continue to do all that I have to do to protect my community.